Amador Vega on Ramon Llull and Ars Combinatoria

What are the historic precedents of the computer? How can compuational thinking be applied to explore artistic creativity and the inner workings of the human soul?

A recent ambitious exhibition at the EPA artlab in Lausanne investigated these questions through the legacy of the great Catalan medieval thinker Ramon Llull - going via renaissance philosophy through to computational art and architecture of our day. We have conversed with curator and international Llull-expert Amador Vega on this exciting topic.

#How do you explain the work and art of Ramon Llull in short to a non-academic public?

It’s no small feat to explain the work of such a singular thinker who, between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, wrote almost 260 books in Catalan, Latin and Arabic, on subjects ranging from philosophy and theology to medicine and law, not to mention novels, poems and autobiographical texts. His primary aim was to design a scientific method based on rational principles that would function as a common ground of understanding between Jews, Christians and Muslims.

As a lay Christian philosopher, Llull was convinced that the true religion was Christianity, but, in contrast to other theologians of the age, he believed that conversion should not be forced upon a people but brought about by winning them over intellectually. His use of personal testimony to convince others of his method, with journeys taking him across the Mediterranean, situates him as a pioneer of intercultural dialogue.

Ramon Lull (1232-1315), Catalan philosopher and mystic - and a pioneer in approaching thinking by mathematical and computational means.

# What is the influence of Lullism and Ars Combinatoria on modern art and computer science about?

The ars combinatoria, understood as a universal language of combinations and permutations of different elements, fascinated philosophers such as Nicholas of Cusa and Giordano Bruno, but it was Leibniz, the philosopher and mathematician, whose Dissertatio de arte combinatoria (1666) pioneered a radical transformation of logic, heaping particular praise on the logic of invention which was in fact already present in Llull.

While not explicitly, numerous artists have echoed this idea, employing a free play of combinations to create, in their artistic production, a language that reproduces certain features in a way that resembles computing. I’d also want to note that there are artists who have responded to the cosmological aspects of Llull’s work, as well as his vision of the different levels or degrees of being, inviting us to consider the relations between art and ecosystems.

15th century manuscript by German philosopher Nicholas of Cusa (1401-1464) - featuring texts and diagrams copied from earlier works by Ramon Llull. In the lower right corner is a diagram with several layers of paper that can be rotated to produce different combinations of symbols and letters

# Llull’s work was informed by a deep mystical vision, while we today often think about computers and algorithms in a very secular context. How did Llull understand the connection between math and the divine?

Llull was a poet and a visionary: that is, he had what we might call an intellectual intuition that led him to comprehend nature – God’s created world – as a collection of signs to be decoded using a formal language. We should not forget that, as a young man, Llull was a troubadour like the Occitan bards and that, to a certain extent, his scientific method is driven by a poetic model.

Structuring it is a system of letters that, when combined following binary rhythms, ternary rhythms, etc… described abstract concepts such as the Names of God (which, for Jews, Christians and Muslims, had the same meaning). This algebraic language also contained what he called ‘algorithmic figures’ that worked as conversion devices, turning certain letters into others and creating a vast network of relationships and interconnectivity.

Nikolaus Joachim Lehmann, Leibniz’ calculating machine from 1690–1720, replica, 1995. © Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum (HNF), Padeborn.

# Do you find lessons to be learned from history that are relevant to the potential perils of todays use of technology - and specifically the development of artificial intelligence?

The great danger of drawing lessons from history is reductionism and the projection of beliefs and affects from one context to another; nevertheless, we can still hope to extract some lesson or other while bearing this in mind.

Llull’s primary objective was not the creation of a technology – a thinking machine – but the conversion of the hearts and minds of men, drawing them closer to the truth. The instruments and techniques he employs, while necessary, were essentially a medium, a support. Yet this support was designed by a highly intelligent mind committed to bringing together truth and reality. To do this required means and instruments, ordered according to a series of specific laws that would guarantee the system’s proper use.

“Llull” lithography, 1988 by Josep Maria Subirachs (1927-2014).

# Do you have a personal favourite item in the exhibition that speaks particularly to you and why?

I find several of the works in the exhibition particularly powerful, as the artists behind them have roundly understood some of the more complex elements of Llull’s thought without sacrificing the freedom to interpret them.

They act like hermeneuts or exegetes, scouring Llull’s ancient declarations for the novelty and newness of our own contemporary languages. In this sense, the work of both Perejaume (‘The Root of the Tree is a Wheel’) and Ralf Baecker (‘Calculating Space’ and ‘Random Access Memory’) seem to me particularly important in showing the extent to which the work of this medieval philosopher and poet continues to nourish our creative imagination.

Amador Vega is a professor of philosopher at the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in. Barcelona, and author of several books within the field of Western mysticism and its relations with aesthetics.

The Thinking Machines exhibition at at the EPFL Art Lab in Lausanne was on between 3rd of November 2018 until 10th of March 2019. The exhibition catalogue can be downloaded here.

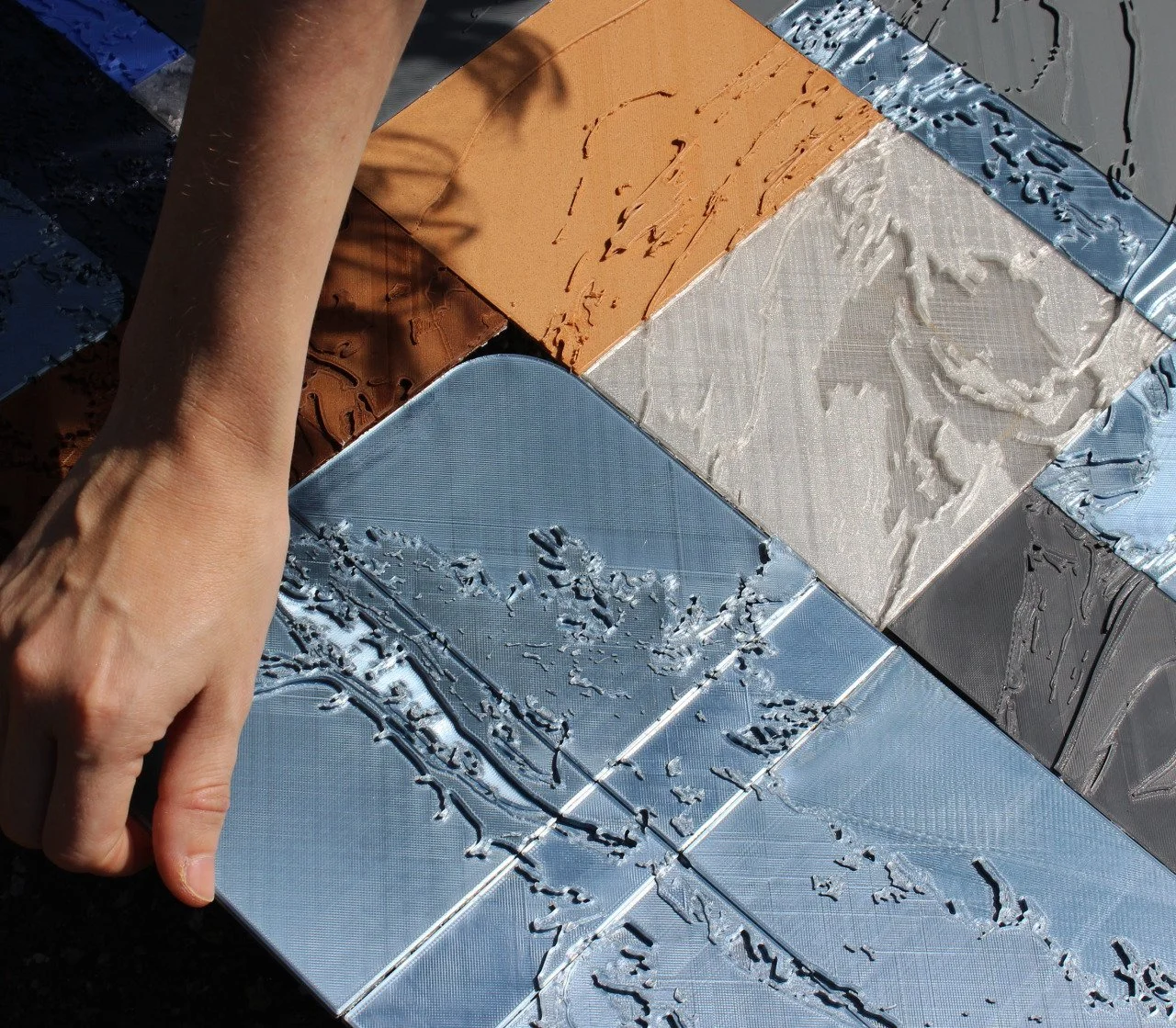

The Root of a Tree is a Wheel.

This installation by Catalan artist Perejaume reflects on two elements that recur throughout the work of Ramon Llull: the wheel (an image that Llull uses in his moving diagrams and that is ideal for the combinatoria), and the tree (the image of the ramification of knowledge and the connection between the lower and upper elements).

The music that accompanies this forest with slowly turning trees consists of texts taken from works from afar as well as traditional Catalan and Corsican folk tunes.

Rechnender Raum (Computing Space)

This installation by Ralf Baecker is a light-weight sculpture, constructed from sticks, strings and little plumbs. At the same time it is a full functional logic exact neural network (*).

http://www.rlfbckr.org/work/rechnender_raum

More Conversations: